"Hey hey hey! Stop that! That's offensive. Indians do not eat monkey brains. And if they do, sign me up, because I am sure they are very tasty... and nutritional." --Michael Scott

*******

Weekend mornings from my childhood all had the same soundtrack. I would wake up to the sounds of static-ridden Indian music blaring from the silver radio outside my bedroom. In the 80s, there was one Indian radio show in Detroit broadcast on the AM dial. Even though the static would rarely dissipate, and the sound quality rivaled that of the moon landing transmission, my parents would blast that show at full volume just to taste some of the nostalgia from the life they left in India. I would often be annoyed, but if I was honest with myself, there was a comfort to seeing my parents enjoy the old songs from their past. If a particularly memorable song was played, my dad would exclaim, "Vah! Vah!" (sort of the Indian equivalent to "THIS IS MY JAM!") his eyes would close, and he'd sway his head to the melody. Oh, and my dad would tune every radio in the house to the crackling Indian show so there was no escape. Every corner of our small ranch house in Royal Oak was filled with the voices of Kishore Kumar, Lata Mangeshkar, Mohammad Rafi and Asha Bhosle. In addition to the musical pleasure for my parents, the sound of Bollywood oldies and Indian Casey Kasem was the perfect transition into my "brown" or Indian weekends.

From Monday to Friday, I had my white life. School days spent with mostly white kids where I would assimilate into a persona of that world. Don't get me wrong, this wasn't some huge Monday morning transformation where I rehearsed saying things like, "Geez Louise!" while locking up my saris. I was pretty much a typical American kid who was never embarrassed about being Indian. However, I learned early on that kids did see me as different and like most kids, I just wanted to belong.

Kindergarten was my first glimpse of what I looked like to the other kids at Oakridge Elementary School. At that time Royal Oak was predominantly white and I was one of about 6 Indian kids in the entire school district (and that includes my older brother). That first day, a little girl looked at me in line for recess and asked, “Do you talk English?” I was a shy kid, so even though inside I was confused, I just looked down at my feet and nodded. “Oh,” she said, “Cuz you don’t look like you know how to talk English.” Mrs. Pedrick called for the girl to keep walking since her inquiry into my language skills was holding up the line. The memory of this girl and her innocent question is vivid; she was missing a tooth, had a lot of freckles and her breath smelled like a rubber band. The memory of my reaction is also clear; I shrugged my shoulders and ran as fast as I could to the swings.

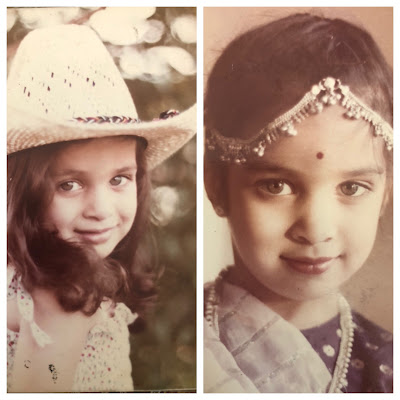

Halloween of my Kindergarten year, my super creative idea for a costume was to dress up as an Indian Girl… yes, an Indian Girl. I remember my mother suggesting Wonder Woman or Strawberry Shortcake, but no, I wanted to wear a Panjabi with braids and bindi on my forehead. Looking back, I’m struck by the irony of my immigrant Indian mother trying to convince me to wear something “American” while I was perfectly content celebrating my heritage on a day where children can be anything. Ah, the bliss of innocence before the agony of self-consciousness.

The day of the Halloween parade, the kids were all confused by my “costume,” and to her credit, Mrs. Pedrick explained how I was dressed in “traditional clothes from her country.” “My country?” I thought, “Isn’t this my country?” I twirled in my Panjabi and gently tapped my forehead to make sure my bindi was still in place. “Sheevani, why don’t you tell us a little about your outfit?” At 5 years old, all I knew was I wearing a Panjabi that my Masi (aunt) brought from India during her last visit. “Well, it’s verrrrry interesting!” Mrs. Pedrick said with her eyes wide. I sat down, and all the superheroes, princesses, cowboys and witches stared at me like I was an alien. One boy’s plastic vampire teeth were hanging out of his mouth as he stared at the sparkly dot on my forehead. If I felt anything other than pride, I certainly do not remember it.

The next year, I wasn’t quite so resilient. In first grade, the kids in my class didn’t see me as an Indian girl; they saw me as a black girl. During a lesson about slavery, a little girl turned around and said, “Your grandpa was a slave.” Her lisp launched a spittle that flew onto my cheek when she said, “slave.” I wasn’t having it. “No, he wasn’t!” I said, “I’m Indian!” The girl shook her head completely dismissing my clarification and turned back around. A boy next to me leaned over and said, "Your skin is brown, that means your black." As if clarifying that detail would change my mind. The frustration went home with me that day and I told my mother why I wasn’t in the best mood after school.

When I think about what my mother did after I tearfully told her what had happened over my after-school bowl of Wheaties, I'm still amazed. She came in after school the next day and asked Mrs. Kampsen to teach the class about India so the kids would understand more about their brown classmate. Mummy spoke slowly and very deliberately, as if she had rehearsed her words. At that point, Bharati Desai had been in the United States for about 10 years. She learned most of her English after she came to this country from night classes at my future high school along with tv shows like Good Times and All in the Family. This immigrant mother saw the pain in her daughter’s eyes and despite her own pressures to assimilate, she made a request unlike any other at Oakridge Elementary in 1984.

Mrs. Kampsen obliged and the following week we learned about India. I sat a little taller on my carpet square as she talked about how India is a country in Asia with a rich culture and spicy foods. The world map was pulled down in front of the blackboard and she pointed out New Delhi and Agra, home of the famous Taj Mahal. Her lesson was simple and sparse, but I was sure this would clear up the confusion. A little boy raised his hand and asked, “Wait, aren’t Indians the people with feathers in their hair?” My teacher clarified the difference between Indians in India ("like Sheevani's family") and the Indians encountered by the pilgrims. The spittle girl turned around and said, “Your grandpa lived in a tee-pee.” Oh, for fuck’s sake.

Around that time, an internal duality of self quietly started and continued to spread through high school. Even when I felt I was making progress, I'd get slammed with not being invited to a party or seeing all my friends at the mall hanging out without me. I still remember in 5th grade a girl telling me she didn't invite me to her summer birthday party because she "wasn't sure if I was allowed to go to parties." When I asked why she said, "I don't know... my mom said your parents would probably say no." Now, did all of these things happen because I wasn't white? Maybe not, but for a sensitive adolescent/teen girl, it was my go-to explanation. No matter which way I leaned, the nagging imposter syndrome crowded any comfort I tried to achieve and eventually, I stopped leaning too far either way.

My "brown weekends" were filled with Indian dance rehearsals, dinner parties, trips to the Indian grocery store to stock up on chutneys and canned mango pulp. That same store carried all the bootlegged Bollywood movies my parents often rented on VHS. No amount of "fix the tracking!" could save some of those prints. Since my mother worked, she would cook a number of dishes on Sunday to last us for the week. If you didn't like leftovers in our house, you were out of luck! My Sunday afternoons were often spent helping my mother make a variety of Indian breads; puris, rotis or parathas. I could never roll them out into perfect circles like she did, but they tasted just the same. Our house always smelled like a warm hug of incense and spice.

Royal Oak’s neighboring cities were where a lot of my Indian friends lived. Troy, in particular, was a hotbed of Indian families who, after saving their money following their arrival in the U.S., upgraded to bigger houses in the upper-middle class suburb. My parents never upgraded. We stayed in Royal Oak. As a child, I wanted so badly to live in Troy. It would have been like going from Molly Ringwald in Pretty in Pink to Molly Ringwald in The Breakfast Club. For my Bharat Natyam (classical Indian dance) lessons each week, I would go to some Indian family’s basement in Troy where I was taught the intricate steps that symbolized the great stories of Hindu mythology. Most of my dance classmates went to school together so they would be chatting about the latest gossip, the upcoming pep rally, who liked whom, which teacher they wanted the next year, etc. I was just their envious dance friend who lived in that poorer, blue-collar city next door.

Even though I had no shortage of school friends, those weekends showed me the impact of having other Indian kids as schoolmates. I never got the sense that my school life was lacking until I'd see those Indian friends bonding over being "the Indian kids" at their schools. Sometimes I would daydream about living in Troy and going to school where seeing an Indian kid was as common as crunchy curled bangs. I just assumed that when they met their white friend's parents, they never heard things like, "Does your mom/dad speak English? Just wanna make sure in case I gotta call them," or "Sorry dear, I just can't say your name," or "What's that dot all about?" Maybe they still got those questions, but in my fantasy of living in Indian-clad Troy, those experiences didn't exist. Did my Indian friends treat me any differently? Other than not including me in their school discussions, not at all. We all got along, but my own projection of feeling different certainly kept me from making deeper connections.

I want to be clear that I wasn't suffering (except in junior high, but I mean, who wasn't?), this was the life I knew and like most other kids, I was just trying to survive my specific struggles of childhood. Honestly, I adapted to the dual-life pretty quickly to the point where on Friday afternoons I couldn't wait to see my Indian friends and on Sunday nights I was excited to dive into the week with my white friends. I don't have some sympathy agenda here, this is just an exploration of where this imposter syndrome comes from. As I get older and try to inch closer to being at peace with my flaws, these examinations into my past help me to understand some of my choices. Was the way I grew up the reason I don't have a large group of friends? Does my past contribute to why I preferred to be a loner on most weekends in high school? Maybe feeling like an outsider in both worlds is why I tend to blame myself if a friendship fades away. Did I have a surge of selfishness in my 20s because I was tired of feeling like a fraud? That's a glimpse into my brain, folks. And yes, I'm exhausted.

Today, my children attend a school with a large Indian population. As a lunch volunteer, I've helped open Tupperware filled with biryani and cleaned up chutney from a kid eating dosas. That stuff warms my heart. Kudos to their immigrant parents for packing lunches without fear of judgement. The world has changed a lot since my skinny brown ass was clinging to whatever commonality it could find depending on the day of the week. The kids today don't even think twice about having friends named Praneeth, Nishant, Divya or Mukti. Since my kids are half Indian, half Polish, they may have their own struggles about where they belong, and I can only hope my childhood can provide some guidance and affirmation that feeling different can be hard, but it's something to embrace. Also, sorry for making you picture my skinny brown child-ass.

I really enjoyed this, Sheevani. Your interpretation of adolescence is incredibly relatable.

ReplyDelete